The TruPS CDO market has shown renewed signs of life over the last six or so months, for the first time really since 2007.

While the rating agencies continue to downgrade these bonds, and while certain serious risks remain to their performance, the market is (finally?) reacting to a number of positive developments in the underlying bank market. Several TruPS CDO securities, we believe, are now grossly mis-rated by the rating agencies. Our analysis suggests that many securities rated CCC or below will pay off in excess of their ratings-implied losses; some are likely to pay off in full.

Default Risk

A key risk for TruPS CDOs remains the default rate on smaller banking institutions. (Aside from banks strictly being pulled into receivership, TruPS CDO noteholders remain exposed to losses that may result on their preferreds to the extent troubled banks restructure, recapitalize or file voluntary petitions for relief under Ch. 11 of the Bankruptcy Code – see for example the cases of AmericanWest, or Builders Bank.)

On the plus side, the rate of bank failures has gone down from 2010. Adjusting for the cohort size – depending on the number of institutions reporting – we’re down from a default rate of approximately 2.05% last year to 1.37% annualized this year, based on the FDIC’s most recent quarterly report (March-end 2011).

This difference is substantial. From the looks of it, one of the key components of this reduction was that bank regulators were more successful in having banks absorbed through a merger process, evading failure: if we consider mergers plus failures, the sum is little different, from 4.62% in 2010 to 4.33% annualized for Q1 2011. But the distribution is now heavier towards the merger side of this equation, implying in the reduced bank failure rate.

The staving off of default, through the merger process or otherwise, almost always proves advantageous to TruPS CDO noteholders.

Balance Sheet Conditions & Outlook

The FDIC notes that “[more] than half of all institutions (56.2 percent) reported improved earnings, and fewer institutions were unprofitable (15.4 percent, compared to 19.3 percent in first quarter 2010),” and that net loan charge-offs (NCOs) have declined for the third consecutive quarter, resulting in an overall 37.5% reduction since March-end 2010. Deposit growth remains strong and the net operating revenues reductions were concentrated at the larger institutions – less of a concern for the average TruPS CDOs which are more heavily exposed to smaller rather than larger banks.

Banks' balance sheets, too, are in better condition: the ratio of noncurrent assets plus other real estate owned assets to assets decreased from 3.44% in 2010 to 2.95%. Also, while the overall employment of derivatives has increased almost 13% over the last year, the heightened exposure is more heavily concentrated among the larger banks. Based on PF2's calculations, if you exclude banks with more than $10bn in assets, you’ll notice a reduction of almost 30% in derivatives exposure over the last year.

These numbers are still much worse than pre-crisis numbers. Historically banks defaulted at an annual rate of approximately 0.36%, on a count basis. We’re at roughly four times that number now. Back in ’06, fewer than 8% of reporting institutions were unprofitable. We’re still at double that number. The ratio of noncurrent assets plus OREO assets to assets was slightly below 0.5% in 2006. We’re sitting at six times that level. But the trends are moving in the right direction – certainly if you’re an investor in the average TruPS CDO.

On the downside, the FDIC’s problem bank list has grown by a not-insignificant amount, from 775 banks (or 10.12% of the cohort) in 2010 to 888 banks (11.72% of cohort) as of March 31, 2011. TruPS CDO noteholders will doubtless hope that these troubled institutions turn around, or are merged or resolved in any other fashion that circumvents default on their trust preferred securities. (For TruPS CDO noteholders exposed to deferring underlying preferreds, the acquisition or merging of the deferring bank by or with a better-capitalized bank brings with it the possibility of the deferral’s cure.)

With the downward trend of bank default rates (and the possibility of deferrals curing), some of the more Draconian bank default probability assumptions can be relaxed, boosting values on TruPS CDO tranches.

We think the market is starting to appreciate this additional "value."

––– a weblog focusing on fixed income financial markets, and disconnects within them

Thursday, June 16, 2011

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

An Aversion to Mean Reversion

Last Wednesday’s Financial Times hosted a scathing column by Luke Johnson, which questions the usefulness of economists, as a whole (see “The dismal science is bereft of good ideas.”)

The column’s title is misleading: Johnson focuses his frustrations only on economists – not economics. Importantly, it is the application of the science, not the science itself, which seems to have caused Johnson's concern.

Indeed the purity of all mathematical sciences can be spoiled by its application. Johnson comments that he “[fails] to see the point of professional economists,” that economists “pronounce on capitalism for a living, yet do not participate in private enterprise, which is its underlying engine.” He ends off his piece by prescribing “[the] best move for the world’s economists would be to each start their own business. Then they would experience at first hand the challenges of capitalism on the front line.”

To be fair, the direct application of economic theory was never intended to satisfy the depths of the dynamic puzzle we put before them, a puzzle for which the answer lay not in the data but in the incentives. [1]

We cannot pretend not to have known that economic models work best in reductionist environments, and that the introduction of complications (like off-balance sheet derivatives) tend to reduce the effectiveness of economic models. Conceptually, once models start to consider too many inter-related variables, or degrees of freedom as statisticians call them, they become so rich and sensitive that no empirical observation can either support or refute them. And so any failures of economists to spot the housing bubble or predict the credit crisis, as Johnson mentions, become our failures too. We would have done better to equip our economists (or academics) with the tools necessary to perform the “down and dirty” analyses that take into account the complex and changing nature of our economy. [2]

Seeing no reason why they ought to have succeeded, we’re perhaps a little more forgiving (than Mr. Johnson) of economists’ shortcomings. But we share his concerns that mathematical sciences are being too directly applied, that the practices and the incentives are being largely ignored.

On Endlessly Assuming “Mean Reversion”

Rather, we ought to encourage our researchers to go into the proverbial field – and to learn to think, and study dynamics, differently.

We can no longer allow ourselves to be informed purely by static analyses of historical data and trends, without seeking a keener appreciation for the underlying dynamics at play. The lazy assumption of mean reversion is simply an assumption, not a rule. When the fundamentals are out of whack – and a direct analysis of data alone cannot tell you that – the market can and will act very differently from a mean-reverting economic model.

Thinking Differently

Given that many market participants have emotions (one could argue that computer algorithms are to an extent emotionless), the tendency for panic or at least the capacity for panic ought to make the direct application of mean reversion models less appealing – and their results less informative, predictive or meaningful.

Ask not “is this a buying opportunity” based on a simple historical trend. But what are the underlying fundamentals? If the game changed based on underlying issues, have they been resolved? Or were they underestimated or overestimated. If the latter is determined after sufficient exploration, one could recommend a "buy." If the former, initiate a "sell." To do otherwise - to simply present a graph and suggest an idea, is folly – it's simply a guess.

Mean reverting economic forecast models continue to be constructed to this day without the thought necessary to support their assumptions (despite the realization that we’re in a very different world).

The outputs, unfortunately, are never better than the inputs.

---------

[1] See our earlier commentary “The Data Reside in the Field”

[2] In light of this fact, it is perhaps troublesome that when questioned by JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon as to the extent of the government's investigation of the effect of its banking regulations, Bernanke purportedly responded "has anybody done a comprehensive analysis of the impact on -- on credit? I can't pretend that anybody really has," ... "You know, it's -- it's just too complicated. We don't really have the quantitative tools to do that." Source

The column’s title is misleading: Johnson focuses his frustrations only on economists – not economics. Importantly, it is the application of the science, not the science itself, which seems to have caused Johnson's concern.

Indeed the purity of all mathematical sciences can be spoiled by its application. Johnson comments that he “[fails] to see the point of professional economists,” that economists “pronounce on capitalism for a living, yet do not participate in private enterprise, which is its underlying engine.” He ends off his piece by prescribing “[the] best move for the world’s economists would be to each start their own business. Then they would experience at first hand the challenges of capitalism on the front line.”

To be fair, the direct application of economic theory was never intended to satisfy the depths of the dynamic puzzle we put before them, a puzzle for which the answer lay not in the data but in the incentives. [1]

We cannot pretend not to have known that economic models work best in reductionist environments, and that the introduction of complications (like off-balance sheet derivatives) tend to reduce the effectiveness of economic models. Conceptually, once models start to consider too many inter-related variables, or degrees of freedom as statisticians call them, they become so rich and sensitive that no empirical observation can either support or refute them. And so any failures of economists to spot the housing bubble or predict the credit crisis, as Johnson mentions, become our failures too. We would have done better to equip our economists (or academics) with the tools necessary to perform the “down and dirty” analyses that take into account the complex and changing nature of our economy. [2]

Seeing no reason why they ought to have succeeded, we’re perhaps a little more forgiving (than Mr. Johnson) of economists’ shortcomings. But we share his concerns that mathematical sciences are being too directly applied, that the practices and the incentives are being largely ignored.

On Endlessly Assuming “Mean Reversion”

Rather, we ought to encourage our researchers to go into the proverbial field – and to learn to think, and study dynamics, differently.

We can no longer allow ourselves to be informed purely by static analyses of historical data and trends, without seeking a keener appreciation for the underlying dynamics at play. The lazy assumption of mean reversion is simply an assumption, not a rule. When the fundamentals are out of whack – and a direct analysis of data alone cannot tell you that – the market can and will act very differently from a mean-reverting economic model.

Thinking Differently

Given that many market participants have emotions (one could argue that computer algorithms are to an extent emotionless), the tendency for panic or at least the capacity for panic ought to make the direct application of mean reversion models less appealing – and their results less informative, predictive or meaningful.

Ask not “is this a buying opportunity” based on a simple historical trend. But what are the underlying fundamentals? If the game changed based on underlying issues, have they been resolved? Or were they underestimated or overestimated. If the latter is determined after sufficient exploration, one could recommend a "buy." If the former, initiate a "sell." To do otherwise - to simply present a graph and suggest an idea, is folly – it's simply a guess.

Mean reverting economic forecast models continue to be constructed to this day without the thought necessary to support their assumptions (despite the realization that we’re in a very different world).

The outputs, unfortunately, are never better than the inputs.

---------

[1] See our earlier commentary “The Data Reside in the Field”

[2] In light of this fact, it is perhaps troublesome that when questioned by JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon as to the extent of the government's investigation of the effect of its banking regulations, Bernanke purportedly responded "has anybody done a comprehensive analysis of the impact on -- on credit? I can't pretend that anybody really has," ... "You know, it's -- it's just too complicated. We don't really have the quantitative tools to do that." Source

Wednesday, June 8, 2011

Is Wall Street Guilty?

“If Wall Street is bilking Main Street on such simple deals–basic trade execution-and yet the only way to recover is to sue, what real chance do individual investors have of getting a fair shake in the financial markets? And what if you add sophisticated computer models, derivatives structuring technology, and secret Cayman Island companies to the mix? Do we have any chance at all?” — Frank Partnoy (1998) in his postscript to F.I.A.S.C.O.

A couple of weeks ago, Bloomberg BusinessWeek ran a story by Roger Lowenstein, entitled “Wall Street: Not Guilty,” that largely absolves Wall Street of criminal culpability for the financial crisis.

This courageous conclusion—and if nothing else one must concede it is courageous—runs counter to popular opinion that malfeasance on Wall Street was an integral cause of the crisis, if not the chief cause. The story widens the debate at a time when a number of vocal critics (including Inside Job director Charles Ferguson and New York Times contributor Jesse Eisinger) are calling for criminal prosecutions.

Putting aside the accuracy of Mr. Lowenstein’s supporting arguments[1], we find it interesting to consider Mr. Lowenstein’s argument against criminal prosecutions from a legal, economic and philosophical perspective.

Society criminalizes conduct to achieve many policy goals, above all, prevention and punishment. (Of course, punishment should have a deterrent effect but it retains significance without regard to its deterrent effect.) Juridically, the primary goals of punishment center on the protection of society from criminal conduct, the stigmatizing of the conduct and the serving of justice to the victim(s).

The economic argument is simple, as it relates to the protection of society. From an economist’s viewpoint, punishment can be described as the “price” a criminal must pay to society for breaking the law, for criminal conduct. This “price” has two elements: the severity of the punishment on the books and the likelihood of its imposition in practice. In proper balance, they work together as deterrents to criminal activity, reducing its incidence. But what happens if we introduce an imbalance between these elements, if our laws create stiff penalties that are never imposed? We already know the answer to this question: when potential criminals believe ex ante that misconduct will not be punished, the marginal wrongdoer is incentivized to seek economic rents from misconduct.

Mr. Lowenstein agrees that “[t]o prosecute white-collar crime is right and proper, and a necessary aspect of deterrence.” However, in the current crisis, he sees a wrong but no wrongdoer: “[T]rials are meant to deter crime—not to deter home foreclosures or economic downturns. And to look for criminality as the supposed source of the crisis is to misread its origins badly.” But the hunt for wrongdoers in this crisis is no mere quest for a scapegoat. Rather, it proceeds from the need to protect society from future crises. This will only happen if punishment deters (or incapacitates) the specific wrongdoer from repeated misconduct and deters the general public from similar misconduct by the example of the punishment of the wrongdoer.

The philosophical analysis is more complex—but worth exploring in a wider context. It forces us to examine how well our present regulatory system is capable of dealing with the special types of problems presented by the complex and opaque world of derivatives dealing, problems with which is it is repeatedly and increasingly being required to cope.

Mr. Lowenstein doesn’t quite make the best philosophical argument against criminal prosecutions in this crisis, but he might have suggested the following: any criminal conduct in this crisis was so wide-spread that no wrongdoer’s action stands alone. If any one wrongdoer had not acted improperly another one would have. In other words, where everyone is guilty, no one is.

In other words, while well-constructed derivatives provided certain wholesome benefits, the opportunity to benefit from abusing derivatives was not limited to a single bank or even a single type of financial institution. Rather it transcended the banks and hedge funds and included all types of market participants, from the buy-side to sell-side to the rating agencies and beyond, and all types of individuals working for those participants. In the end, the entire profit maximization motive and the human nature from which it proceeds must be put on trial, so that ultimately we all find ourselves sitting right next to every other defendant in the dock.

Thus, a defense might argue that the “system” seems to have encouraged (and rewarded) wide-spread misconduct and that, given the existence of such a dysfunctional dynamic, one ought to excuse a defendant's acting as a willing participant (or instrument) in this unjust system, if for no other reason than to advance his or her self interests, or lofty ambitions.

The philosophical response may simply be this: an abyss exists between actual wrongdoing and potential wrongdoing. Those who kill while part of a mob really are different from those who are just part of the mob.

But while philosophically that response might appear to suffice, legally there remain certain challenges. Among other things, a prosecutor has to prove both components of a criminal act: criminal conduct and the requisite mental state. The requisite mental states—intentional, knowing, reckless or even negligent conduct—may vary by jurisdiction and they may pose a barrier to the extent they require a determination of the defendant’s level of deviation from that of the ordinary person in a similar environment. (The similarly improper conduct of many or all parties surrounding the defendant may obscure the analysis of a “punishable mental state.”)

But they should not prevent prosecution: the critical question is not “Shall we prosecute?” but “Whom shall we prosecute?”

Nor does the argument hold weight that a subordinate can excuse her role as a mere functionary carrying out the role of her superior. Whether the defendant was only a tiny cog in the machinery, or the motor driving the faulty operation, the relative importance to the resulting order of magnitude of the misconduct serves only to help define the gravity of the sentence imposed—not the probability of its imposition.

17th century Dutch jurist and statesman Hugo Grotius, paraphrasing an earlier Roman authority, explained that "punishment is necessary to defend the honor or the authority of him who was hurt by the offence so that the failure to punish may not cause his degradation."

Given the continued proliferation of improper derivatives dealing, it is punishment alone that can protect our society for future wrongdoing—through stigmatizing the improper acts and by serving as a material deterrence for potential wrongdoers. In this way, restitution will meet the material concerns of the victims of these crimes—the tax-payers.

--------------

[1] The facts have been argued by, among others, Ryan Chittum and Prof. William Black.

Thursday, May 19, 2011

A Telling Tale of Two Tables

Just how difficult is it to measure ratings performance, and how useful are the measures, really?

There are certain difficulties we all know about – having to rely on the ratings data being given to you by the parties whose performance you’re measuring. So there is naaturally the potential for the sample to be biased or slanted, and that’s very difficult to uncover. (We’ve discussed this hurdle at great length here.)

The next issue we’ve written about is the inability to separate the defaulting assets from those that didn’t default. In our regulatory submission, we called for transparency as to what happened to each security BEFORE its ratings was withdrawn (see Transparency of Ratings Performance).

Let’s have a look at a stunning example today that brings together a few of the challenges, and leaves one with a few unanswered questions as to the meaningfulness of ratings performance, as it's being currently displayed, and the incentives rating agencies have to update their own ratings.

Here’s a Bloomberg screenshot for the rating actions on deal Stack 2006-1, tranche P.

Starting from the bottom up, it seems Moody’s first rated this bond in 2006 whereas Standard & Poor’s first rated it in 2007. If we try to verify this on S&P’s website for history, we come to realize how difficult it can be to verify:

So let’s suppose everything about the Bloomberg chart is accurate.

As verified on their website, Moody’s rated this bond Aaa in August ’06 and acted no further on this bond until it withdrew the rating in June 2010. (They don’t note whether the bond paid off in full, or whether it defaulted.)

S&P, meanwhile, shows its original AAA rating of 2007 being downgraded in 2008 (to BBB- and then to B-) and in 2009 to CC and again in 2010 to D, which means it defaulted (according to S&P).

For Moody’s, the first year for which the bond remains in the sample for a full year is 2007; thus, it wouldn’t be included in 2006 performance data. For S&P, the first complete year is 2008.

So if we consider how Moody’s would demonstrate its ratings performance on this bond, it would say:

Year 2007: Aaa remains Aaa

Year 2008: Aaa remains Aaa

Year 2009: Aaa remains Aaa

Year 2010: Aaa is withdrawn (WR)

No downgrades took place, according to Moody’s … while at the same time S&P shows it as having defaulted:

Year 2008: AAA downgraded to B-

Year 2009: B- downgraded to CC

Year 2010: CC downgraded to D

Here’s what their respective performance would look like, if one were to apply their procedures (at least as far as we understand them):

There are certain difficulties we all know about – having to rely on the ratings data being given to you by the parties whose performance you’re measuring. So there is naaturally the potential for the sample to be biased or slanted, and that’s very difficult to uncover. (We’ve discussed this hurdle at great length here.)

The next issue we’ve written about is the inability to separate the defaulting assets from those that didn’t default. In our regulatory submission, we called for transparency as to what happened to each security BEFORE its ratings was withdrawn (see Transparency of Ratings Performance).

Let’s have a look at a stunning example today that brings together a few of the challenges, and leaves one with a few unanswered questions as to the meaningfulness of ratings performance, as it's being currently displayed, and the incentives rating agencies have to update their own ratings.

Here’s a Bloomberg screenshot for the rating actions on deal Stack 2006-1, tranche P.

Starting from the bottom up, it seems Moody’s first rated this bond in 2006 whereas Standard & Poor’s first rated it in 2007. If we try to verify this on S&P’s website for history, we come to realize how difficult it can be to verify:

So let’s suppose everything about the Bloomberg chart is accurate.

As verified on their website, Moody’s rated this bond Aaa in August ’06 and acted no further on this bond until it withdrew the rating in June 2010. (They don’t note whether the bond paid off in full, or whether it defaulted.)

S&P, meanwhile, shows its original AAA rating of 2007 being downgraded in 2008 (to BBB- and then to B-) and in 2009 to CC and again in 2010 to D, which means it defaulted (according to S&P).

For Moody’s, the first year for which the bond remains in the sample for a full year is 2007; thus, it wouldn’t be included in 2006 performance data. For S&P, the first complete year is 2008.

So if we consider how Moody’s would demonstrate its ratings performance on this bond, it would say:

Year 2007: Aaa remains Aaa

Year 2008: Aaa remains Aaa

Year 2009: Aaa remains Aaa

Year 2010: Aaa is withdrawn (WR)

No downgrades took place, according to Moody’s … while at the same time S&P shows it as having defaulted:

Year 2008: AAA downgraded to B-

Year 2009: B- downgraded to CC

Year 2010: CC downgraded to D

Here’s what their respective performance would look like, if one were to apply their procedures (at least as far as we understand them):

Friday, May 13, 2011

Adverse Selection? No Problem!

A section from their rating methodology piece "Moody’s Approach To Rating U.S. Bank Trust Preferred Security CDOs" describes its procedures for ensuring the quality of bank preferreds being bought by CDO managers (S&P / Fitch have something similar). The section reads:

Alas...

"In order to control for [adverse selection of banks by the arranger of CDOs], Moody's takes a four-step approach for banks that are not rated by Moody's.

First, each bank should satisfy the following prescreening attributes:

- Financial Institution insured by the Bank Insurance Fund or Saving Association Insurance Fund.

- Five years minimum of operating history.

- Minimum asset size of $100 million.

- Not under investigation by any regulatory body.

[additional steps omitted in the name of brevity]

- No restrictions placed on its operations by any regulatory body."

Alas...

Labels:

Banks,

CDO,

Collateral Managers,

Rating Agencies,

Structured Finance,

TruPS CDOs

Tuesday, May 10, 2011

Pricing Transparency

Professor Allan Meltzer argues, in yesterday’s WSJ article BlackRock's 'Geeky Guys' Business, that BlackRock Solutions’s pricing process “should all be open” and that “[they] may be doing things honestly and above board, but we won’t see that unless we see how they got the numbers.”

While legislators and supervisors scurry to plug the holes created by the absence of both balance sheet and asset transparency, the final piece of the puzzle – pricing transparency – remains largely unattended to.

It is this final element, the lack of pricing transparency, that concerns Prof. Meltzer. Right now, hedge funds, banks and insurance companies can all carry the same asset at a different price. In illiquid markets, the price differential between two price providers can be extraordinary, creating an opportunity for lesser-regulated financial institutions to profit handsomely from the regulatory arbitrage available, at the expense of their more heavily-regulated counterparts.

As with “ratings shopping” where market participants seek the highest ratings on their securities, investors are financially incentivized to seek out the highest value they can find for each security. Funds’ performance (and often their managers' bonuses) is directly determined from the valuations of their assets. Stronger performance, whether real or artificial, can even help a fund or company raise new capital.

Thus, there remains significant potential for derivatives mispricing. One could even argue that the potential for mispricing is heightened when the price provider offers additional advisory services to the client. Given the substantial fees and margins that may be earned on the advisory side, a conflicted price provider may be more open to accommodating a client’s price haggling to win or maintain it as a client.

Prof. Meltzer’s goal for pricing transparency would hone in on, perhaps eliminate, numerous possible sources for deliberate mispricing (see list of contested pricings here). While we fear it may be prove an insurmountable hurdle to require pricing providers to share transparency as to their methods, we feel strongly that an opportunity exists now for market regulators to ensure the consistency of prices used. (See Central Pricing Solution here.)

Absent complete pricing transparency, the usage of consistent prices would serve to increase investor confidence as to the adequacy of financial institutions’ balance sheets. A requirement for all constituents supervised by the same regulatory body to apply the same price can discourage price haggling, or price shopping.

While legislators and supervisors scurry to plug the holes created by the absence of both balance sheet and asset transparency, the final piece of the puzzle – pricing transparency – remains largely unattended to.

It is this final element, the lack of pricing transparency, that concerns Prof. Meltzer. Right now, hedge funds, banks and insurance companies can all carry the same asset at a different price. In illiquid markets, the price differential between two price providers can be extraordinary, creating an opportunity for lesser-regulated financial institutions to profit handsomely from the regulatory arbitrage available, at the expense of their more heavily-regulated counterparts.

As with “ratings shopping” where market participants seek the highest ratings on their securities, investors are financially incentivized to seek out the highest value they can find for each security. Funds’ performance (and often their managers' bonuses) is directly determined from the valuations of their assets. Stronger performance, whether real or artificial, can even help a fund or company raise new capital.

Thus, there remains significant potential for derivatives mispricing. One could even argue that the potential for mispricing is heightened when the price provider offers additional advisory services to the client. Given the substantial fees and margins that may be earned on the advisory side, a conflicted price provider may be more open to accommodating a client’s price haggling to win or maintain it as a client.

Prof. Meltzer’s goal for pricing transparency would hone in on, perhaps eliminate, numerous possible sources for deliberate mispricing (see list of contested pricings here). While we fear it may be prove an insurmountable hurdle to require pricing providers to share transparency as to their methods, we feel strongly that an opportunity exists now for market regulators to ensure the consistency of prices used. (See Central Pricing Solution here.)

Absent complete pricing transparency, the usage of consistent prices would serve to increase investor confidence as to the adequacy of financial institutions’ balance sheets. A requirement for all constituents supervised by the same regulatory body to apply the same price can discourage price haggling, or price shopping.

Monday, May 2, 2011

The Data Reside in the Field

In the New York Times' “Needed: A Clearer Crystal Ball” (Sunday Business pg. 4) professor Robert Shiller claims that if we sharpen our risk measurement tools we will better understand the risk of another financial shock. He argues that improved data collection can substantially increase the predictive power of our financial models.

As mathematicians we must agree with his sentiment: more complete data is always useful. But as market participants we wonder if professor Shiller has missed out on a valuable lesson to be learnt from this financial crisis.

One key lesson was that the source of the failure was neither data-driven nor model-driven, but rather a direct result of the expected behavior of poorly incentivized parties.

In fact, one could argue that for the large part the data were comprehensive. The models were highly sophisticated, perhaps too sophisticated. But what caused the crisis was that originating parties were financially rewarded for structuring and selling low quality mortgage loans. The incentive was clear and by mid-2005 the FBI was already commenting on the pervasive and growing nature of mortgage fraud.

Misrepresented financial documentation skews the data and cannot be spotted simply by poring over ever more abundant realms of data: you have to go into the field itself to follow the incentives.

The financial downturn was made worse by financial institutions’ lack of confidence in the creditworthiness of their counterparts. Absent a level of certainty as to the true nature of others’ balance sheets, a lending freeze precipitated an illiquidity crisis. But a more thorough examination of data won’t tell you what resides off-balance sheet: you have to understand the prevailing accounting environment (that led to the mechanical reproduction of the negative basis trade) and the fundamental nature of the opaque shadow banking system.

It is a concern that intellectuals and academics risk being lulled into a false sense of security based on their access to copious amounts of statistical data.

Copious analysis of imperfect data is unlikely, alone, to help our regulators hone in on an inevitable crisis – much less prevent it. Let's not strive to build complex economic models whose success hinges on sensitive data. Let us rather encourage a keener appreciation of the limitations of data, the intentional proliferation of informational asymmetries, and the incentives that can cause a meltdown.

As mathematicians we must agree with his sentiment: more complete data is always useful. But as market participants we wonder if professor Shiller has missed out on a valuable lesson to be learnt from this financial crisis.

One key lesson was that the source of the failure was neither data-driven nor model-driven, but rather a direct result of the expected behavior of poorly incentivized parties.

In fact, one could argue that for the large part the data were comprehensive. The models were highly sophisticated, perhaps too sophisticated. But what caused the crisis was that originating parties were financially rewarded for structuring and selling low quality mortgage loans. The incentive was clear and by mid-2005 the FBI was already commenting on the pervasive and growing nature of mortgage fraud.

Misrepresented financial documentation skews the data and cannot be spotted simply by poring over ever more abundant realms of data: you have to go into the field itself to follow the incentives.

The financial downturn was made worse by financial institutions’ lack of confidence in the creditworthiness of their counterparts. Absent a level of certainty as to the true nature of others’ balance sheets, a lending freeze precipitated an illiquidity crisis. But a more thorough examination of data won’t tell you what resides off-balance sheet: you have to understand the prevailing accounting environment (that led to the mechanical reproduction of the negative basis trade) and the fundamental nature of the opaque shadow banking system.

It is a concern that intellectuals and academics risk being lulled into a false sense of security based on their access to copious amounts of statistical data.

Copious analysis of imperfect data is unlikely, alone, to help our regulators hone in on an inevitable crisis – much less prevent it. Let's not strive to build complex economic models whose success hinges on sensitive data. Let us rather encourage a keener appreciation of the limitations of data, the intentional proliferation of informational asymmetries, and the incentives that can cause a meltdown.

Friday, April 22, 2011

Ratings Reversals

Back in our December 2010 piece (The Psychological Biases of Holding Downgraded Bonds) we commented on what was to us a rather unusual trend in the collateralize loan obligation space, where these bonds were being downgraded at a time when their fundamentals were already (generally) rebounding.

The downgrading (if it is premature) of a long-term bond only to subsequently upgrade it falls broadly within what is referred to as a “Type II” ratings error.

Holding lower-rated bonds can be more expensive for investors. This may encourage holders to sell the bonds to the extent the cost of funding the lower-rated bonds is too high, or they may even become forced sellers to the extent the lower ratings fall outside of their investment guidelines or their vehicles’ eligibility criteria. Thus, in addition to the (rather unfortunate) increased cost of funding on a downgraded bond, one may be forced to sell the bond at an inopportune time, only to see the bond subsequently re-upgraded.

Ratings reversals can include downgrades followed soon after by upgrades, or upgrades accompanied by subsequent downgrades.

Examples of Moody’s ratings reversals:

1 - Gresham Street CDO Funding 2003 class B notes (CUSIP 39777PAB9): Originally rated Aaa in 2003. Downgraded (Moody’s) to A1 in Aug. 2009. Upgraded to Aaa in May 2010. (S&P maintained rating at AAA throughout.)

2 - Halcyon Loan Investors tranche B (CUSIP 40536YAJ3): Downgraded from A2 to Ba1 (March ’09) to B3 (June ‘09); upgraded back to Ba3 (May ’10) and Ba1 (Dec. ’10).

Happy Easter everybody!

- PF2

----------

For more on this topic, click here.

“[One] rating agency began downgrading collateralized loan obligation (CLO)securities between September 2009 and May 2010, well after the market shock had ended, with loan prices generally having begun returning to 'normal' levels in December 2008. Depending on what indices you examine, loan prices generally went up roughly 40% during calendar year 2009, and this trend has continued in 2010. CLO prices improved too, as have their underlying portfolios. So while the rating agency was aggressively downgrading almost 3,000 bonds during this time period, the underlying loan market and the CLOs themselves were markedly improving.”Moody’s recently produced some very informative data on their ratings reversal rates in structured finance. Not surprisingly – at least to to us and the avid readers of our blog – CLOs lead the list of ratings reversals, at a rate of approximately 5 times that of other CDOs (excluding CLOs) and more than 6 times the rate of all global structured finance ratings provided by Moody’s.

The downgrading (if it is premature) of a long-term bond only to subsequently upgrade it falls broadly within what is referred to as a “Type II” ratings error.

Holding lower-rated bonds can be more expensive for investors. This may encourage holders to sell the bonds to the extent the cost of funding the lower-rated bonds is too high, or they may even become forced sellers to the extent the lower ratings fall outside of their investment guidelines or their vehicles’ eligibility criteria. Thus, in addition to the (rather unfortunate) increased cost of funding on a downgraded bond, one may be forced to sell the bond at an inopportune time, only to see the bond subsequently re-upgraded.

Ratings reversals can include downgrades followed soon after by upgrades, or upgrades accompanied by subsequent downgrades.

Examples of Moody’s ratings reversals:

1 - Gresham Street CDO Funding 2003 class B notes (CUSIP 39777PAB9): Originally rated Aaa in 2003. Downgraded (Moody’s) to A1 in Aug. 2009. Upgraded to Aaa in May 2010. (S&P maintained rating at AAA throughout.)

2 - Halcyon Loan Investors tranche B (CUSIP 40536YAJ3): Downgraded from A2 to Ba1 (March ’09) to B3 (June ‘09); upgraded back to Ba3 (May ’10) and Ba1 (Dec. ’10).

Happy Easter everybody!

- PF2

----------

For more on this topic, click here.

Wednesday, April 13, 2011

Split Ratings

Given the high correlation between security prices and their ratings, we wanted to follow up on some of our prior pieces that contemplated the wide discrepancies between ratings opinions provided on certain securities (see for example here and here). Split ratings, of course, present trading opportunities.

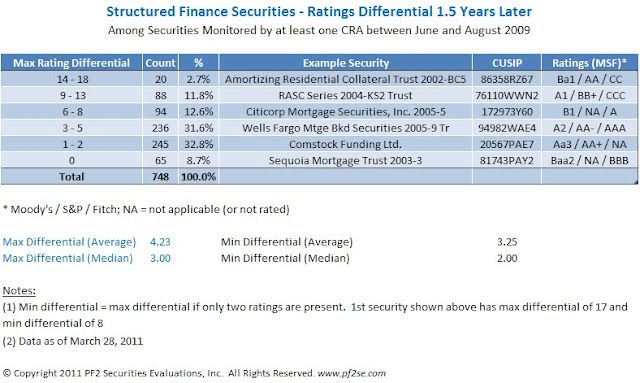

Our analysis considered securities that were acted upon by a single rating agency between June and August of 2009. We then had a look at the average ratings split as of March 28 this year: one and a half years later. The outcome was quite astonishing.

While at inception the rating agencies seem typically to achieve the same rating, down the line they tend to substantially disagree with one another. (We have broken the differential down depending on how many rating agencies rated each security. If all three of Moody's, Fitch and S&P rated the security, we'll show both a max split and a minimum split. If only two raters rated the security as of March 28, 2011, the max split equals the min split.) The average max differential: 4.23 rating subcategories (or "notches"). The median differential - 3 notches. One rating subcategory would be the difference between a AAA and a AA+.

This table shows examples of the 748 structured finance securities considered in our database at each ratings split level, including one of the 20 securities on which there was a ratings differential of between 14 and 18 ratings subcategories.

Our analysis considered securities that were acted upon by a single rating agency between June and August of 2009. We then had a look at the average ratings split as of March 28 this year: one and a half years later. The outcome was quite astonishing.

While at inception the rating agencies seem typically to achieve the same rating, down the line they tend to substantially disagree with one another. (We have broken the differential down depending on how many rating agencies rated each security. If all three of Moody's, Fitch and S&P rated the security, we'll show both a max split and a minimum split. If only two raters rated the security as of March 28, 2011, the max split equals the min split.) The average max differential: 4.23 rating subcategories (or "notches"). The median differential - 3 notches. One rating subcategory would be the difference between a AAA and a AA+.

This table shows examples of the 748 structured finance securities considered in our database at each ratings split level, including one of the 20 securities on which there was a ratings differential of between 14 and 18 ratings subcategories.

Thursday, April 7, 2011

Contested Pricings List

The capacity for price manipulation or price inflation presents a major challenge for the market to overcome, especially in the illiquid markets where live trading data are seldom made available to the general public. Like "ratings shopping," investors may be incentivized towards seeking the highest price, or most accommodating price provider, for their securities.

We will continue to maintain this growing database of situations in which parties disagree as to the prices used, or pricing practices employed.

- Apr. 2021: Behind the Mysterious Demise of a $1.7 Billion Mutual Fund: "The Infinity Q Diversified Alpha Fund disclosed in filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission valuations of investments that in at least three instances were incorrect or inconsistent with market conditions, said traders and academics."

- Jan. 2021: Exxon Draws SEC Probe Over Permian Basin Asset Valuation: "The Securities and Exchange Commission launched an investigation of Exxon Mobil Corp. after an employee filed a whistleblower complaint last fall alleging that the energy giant overvalued one of its most important oil and gas properties, according to people familiar with the matter."

- Apr. 2019: Direct Lending Investments, LLC: "According to the SEC’s complaint, Direct Lending, through its owner and CEO Brendan Ross, engaged in a multi-year effort to manipulate the performance data for one of Direct Lending’s significant investments in loans made by an online small business lender. This materially inflated Direct Lending’s assets under management and its reported returns, and resulted in approximately $11 million in over-charges of management and performance fees to its private funds."

- Jun. 2018: Hedge Fund Adviser to Pay $5 Million for Compliance Failures Related to Valuation of Fund Assets: "An SEC investigation found that Colorado-based investment adviser Deer Park Road Management Company LP, in connection with its flagship STS Partners’ fund which has been ranked as one of the most consistent performing hedge funds in the country, failed to have policies and procedures to address the risk that its traders were undervaluing securities and selling for a profit when needed. The firm also failed to guard against its traders’ providing inaccurate information to a pricing vendor and then using the prices it got back to value bonds. CIO Scott Burg oversaw the valuation of certain assets in the flagship fund and approved valuations that the traders flagged as “undervalued” with notations to “mark up gradually.” Also overseeing valuation was a committee comprised of the principal’s relatives and others without relevant expertise."

- Mar. 2018: A private equity star's picks shine ... until cash-out time: "Since Catalyst launched its second fund in 2006, however, the firm’s record of double-digit annual returns has been based largely on its own assessments of improvements to its stable of distressed companies. When put to the test, at least four of Catalyst’s major assets have been unable to find buyers at the firm’s valuations, based on a Reuters review of Catalyst’s portfolio, multiple communications from Catalyst to its clients and regulatory filings, as well as interviews with people familiar with Catalyst’s operations, academics and financial analysts."

- Mar. 2018: Glaucus targets Blue Sky Alternative Investments as next Australian short: "The hedge fund argues Blue Sky stock is over-valued, and worth no more than $2.66 a share. Further, Blue Sky is alleged to have overstated the amount of assets under management (AUM) that are capable of earning fees, which Glaucus asserts is "at most $1.5 billion" and not the $3.9 billion the company reported at its February results. Central to its thesis is that Blue Sky has succeeded by "aggressively" marking up the value of unlisted assets so it can charge higher fees and flatter its returns, lifting its share price."

- Feb. 2018: Credit Suisse hit by U.S. lawsuit over writedowns, says case "without merit": "[A] class action lawsuit in New York accuses the bank, Thiam and Mathers of giving false and misleading information about risky investments that led to a drop in Credit Suisse’s share price, costing investors millions, the newspaper reported."

- Feb. 2018: Nomura Suspends Two Junk-Bond Traders in London: "In the decade since the financial crisis, banks around the world have paid more attention to how they value harder-to-trade debt securities, such as those backed by mortgages, or loans financing leveraged takeovers. Regulators and banks have cracked down on suspected instances of so-called mismarking, in which traders misrepresent the true value of securities."

- Feb. 2018: Deer Park Road Draws SEC Probe Over Bond Valuations: "The Securities and Exchange Commission is questioning why the fund priced certain debt positions below market norms, said one of the people, who asked not to be identified because the probe isn’t public. The inquiry focuses on the pricing of hard-to-value residential mortgage-backed securities, some of which can go months without trading."

- Dec. 2017: SEC Probes If Banks Helped Hedge Funds Inflate Returns: "The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission is now investigating whether some banks crossed the line to win business by offering hedge funds bogus price quotes on hard-to-value bonds, said two people familiar with the matter. The SEC’s concern: As a reward for helping hedge funds make money -- by submitting quotes at requested levels -- banks got trades steered their way."

- Dec. 2017: Intrepid writes down mining properties: "ASIC notes the decision by Intrepid Mines Limited (Intrepid) to make a $16.1 million impairment charge against its Zambian mining properties in its financial report for the half-year ended 30 June 2017. ... Intrepid announced a subsequent sale of its Zambian assets for $4.75 million plus $1 million deferred contingent payments on 12 December 2017, resulting in a further loss."

- Oct. 2017: Rio Tinto, Former Top Executives Charged With Fraud: "The Securities and Exchange Commission today charged mining company Rio Tinto and two former top executives with fraud for inflating the value of coal assets acquired for $3.7 billion and sold a few years later for $50 million."

- Oct. 2017: Ex-Third Point Partner’s Bond Trades Focus of SEC Probe: "U.S. regulators are investigating whether a top trader who left Dan Loeb’s Third Point hedge fund earlier this year contributed to the mispricing of hard-to-value mortgage bonds, two people familiar with the matter said. The Securities and Exchange Commission is probing whether former Third Point partner Keri Findley caused the thinly traded bonds to be undervalued, said the people who asked not to be named because the probe isn’t public. Findley, 35, left the $18 billion firm in February, telling people who had direct communications with her that she was retiring and moving to California."

- Oct. 2017: RBS to pay $44 million to settle U.S. charges it defrauded customers: "RBS will pay a $35 million fine, plus at least $9.09 million to more than 30 customers, including Pacific Investment Management Co, Soros Fund Management and affiliates of Bank of America, Barclays, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley. Prosecutors said that from 2008 to 2013, RBS cheated customers by lying about bond prices, charging commissions it did not earn and concealing the fraud in an effort to boost profit at the customers’ expense."

- Aug. 2017: SEC Order: In the Matter of KPMG LLP AND JOHN RIORDAN, CPA: "This case involves improper professional conduct and securities law violations by KPMG and Riordan relating to a review and audit of the financial statements of Miller Energy Resources, Inc. (“Miller Energy”). During its fiscal 2010, Miller Energy acquired certain oil and gas interests located in Alaska (the “Alaska Assets”) for an amount the company estimated at $4.5 million and then subsequently reported those assets at an inflated value of $480 million in its fiscal 2010 financial statements. This asset valuation violated generally accepted accounting principles (“GAAP”) and overstated the fair value of the assets by hundreds of millions of dollars."

- Aug. 2017: One of Canada’s largest private-equity firms accused of fraud: "Canadian securities regulators received four independent whistleblower complaints against a multibillion-dollar investment firm Catalyst Capital Group Inc., The Wall Street Journal reported ... The case was brought to the country’s leading securities regulator — Ontario Securities Commission. According to the complaints it was artificially inflating the value of some of its assets and deceiving borrowers about the terms of loans it made."

- May 2017: Hedge Funds Are Facing a U.S. Criminal Probe Over Bond Valuations: "The witness, a former broker named Frank DiNucci Jr., said under oath that he provided bogus quotes to a trader at a mortgage bond fund, Premium Point Investments LP. DiNucci agreed to plead guilty last month in Manhattan federal court to conspiracy and fraud and says he has been cooperating with a criminal probe by New York prosecutors into Premium Point." ...“I would extend marks to make them seem like they were my own,” DiNucci told the federal jury in Hartford. The goal was to “increase the number of trades we would do with this particular client,” he said.

- Apr. 2017: Lehman Suit Seeks Return of $2 Billion in 'Phantom' Citi Fees: "The trial opens a rare window into the frenzied weekend before Lehman’s bankruptcy filing on Sept. 15, 2008. Banks were supposed to use a Sunday trading session to mitigate damage to the financial system by reducing their exposure to the bank. Lehman, which first sued over the $2 billion in 2012, claims that Citigroup efficiently hedged its risks, but went on to inflate its claim by marking its books to its benefit." ... "Marc Pagano, who ran Citigroup’s emerging-markets business at the time and was involved in closing out some of his group’s trades, was asked in a phone conversation -- a recording of which was played in court Wednesday -- whether traders were supposed to mark their books under a different methodology than usual. “Yeah, one night. One night only,” Pagano said in the call. “We only deviated one night.”

- Feb. 2017: Mortgage investor Premium Point discloses SEC probe: Premium Point Investments LP is under investigation by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission over the valuation of structured products and other assets held by its funds, according to a letter sent to clients of the New York-based investment firm.

- Jan. 2017: SEC Reviews Bond Trades by Hedge Funds, Devaney’s Firm: At issue, the people said, are trades between hedge funds -- including Candlewood Investment Group -- and United Capital Markets, a brokerage owned by John Devaney. Investigators at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission are trying to determine if the prices in small transactions were reasonable or were inflated to allow the parties to record gains on bigger holdings of the securities, according to the people. Devaney said there has been no suggestion by regulators that his firm engaged in misconduct.

- Dec. 2016: ECB Found Deutsche Bank Risk Management Weakness: "A European Central Bank inspection of Deutsche Bank AG’s risk controls found deficiencies in derivatives and complicated financial bets that raise questions about pricing processes at the German lender, Il Sole 24 Ore reported."

- Dec. 2016: Wall Street Cop Asks Money Managers To Reveal Silicon Valley Valuations: "Federal securities regulators are intensifying efforts to determine how large U.S. money managers value some of the best-known private technology companies, such as Uber Technologies Inc. and Airbnb Inc. In recent weeks, the Securities and Exchange Commission sent letters to or spoke with several mutual fund firms including T. Rowe Price Group Inc. and Fidelity Investments, according to people familiar with the matter."

- Oct. 2016: Deutsche Bank Said to Review Valuations of Inflation Swaps: "The bank is looking at valuations on a type of derivative known as zero-coupon inflation swaps, said the people, who asked not to be identified because the matter is confidential. After finding valuations that diverged from internal models, it began questioning traders, the people said."

- Aug. 2016: Legal Fight Escalates Over Tech Startup’s Financials: "Mr. Biederman holds 64,166 Domo shares that would be worth $540,919 at the $8.43-per-share price where Domo sold stock to investors last year. But some mutual-fund investors have since marked down their Domo shares, according to The Wall Street Journal’s Startup Stock Tracker. Morgan Stanley said Domo shares were worth $5.04 a share as of May."

- Aug. 2016: Former Deutsche Bank Trader Fined $50,000 by SEC Over Valuations: "A former Deutsche Bank AG trader agreed to settle a U.S. regulator’s allegations that he mis-marked loans tied to commercial-mortgage-backed securities to boost his profits" ... "The SEC has made policing bond valuations a priority. The agency and the Justice Department have brought civil and criminal cases against traders for lying about bond prices to customers. The SEC is using algorithms to comb through bond trading and has found billions of dollars worth of problematic transactions."

- Aug. 2016: U.S. mutual funds boost own performance with unicorn mark-ups: "The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has been asking mutual fund companies how they value their stakes in companies like Uber, Pinterest Inc and Airbnb. The regulator is worried investors could get hurt in case of a sharp tech downturn, according to two people familiar with the SEC's queries."

- July 2016: Fraud Probe Ricochets Through Platinum Partners: "Among questions investigators seek to answer is whether Platinum misstated values of some holdings, the people familiar with the probe said. Platinum spokesman ... defended the firm’s auditing and valuation methods and said it stands behind its performance record."

- July 2016: LendingClub Fund Has Its Version of June Swoon: "LendingClub also said in the filing that LC Advisors hadn't followed standard accounting rules when it was determining the value of the loans in its portfolio as well as their monthly returns. Investors affected by the adjustments would be reimbursed around $800,000,...."

- June 2016: CMBS Servicers Sued in Fair-Value Option Case for 'Flawed' Appraisal: An investor in a 2007 CMBS transaction has sued the deal's master and special servicers, arguing that they breached their obligations under the deal's pooling and servicing agreement when they allowed a collateral $84.8 million loan to be sold using a fair-value purchase option.

- June 2016: ASIC calls on directors to apply realism and clarity to financial reports. "ASIC continues to find impairment calculations based on unrealistic cash flows and assumptions, as well as material mismatches between the cash flows used and the assets being tested for impairment.... Fair values attributed to financial assets should also be based on appropriate models, assumptions and inputs."

- May 2016: Wall Street Cops to Hedge Funds: Treat Investors Better: "Regulators are looking into whether a firm employed by RD Legal as its independent valuation agent, Pluris Valuation Advisors LLC, ever contested any of the firm’s preferred valuations, people familiar said."

- May 2016: Banks Sued by Investor Over Agency-Bond Rigging Claims. "The lawsuit... accuses traders of colluding with one another to fix prices at which they bought and sold SSA bonds in the secondary market. It adds the threat of possible triple damages available under U.S. antitrust law for investors harmed by any illegal price-fixing."

- Mar. 2016: A $7 billion hedge fund says it's being investigated by the SEC and the US Department of Justice: "They have requested information from several years ago regarding the valuation of certain securities in the firm's credit fund which was closed in 2013,..."

- Feb. 2016: Loan Valuations Draw Scrutiny: Some firms are marking down securities faster than others

- Nov. 2015: Regulators Look Into Mutual Funds’ Procedures for Valuing Startups

- Sept. 2015: Canadian Pension Fund Says It Was Cheated By Boaz Weinstein's Saba Capital

- May 2015: SEC Charges Deutsche Bank With Misstating Financial Reports During Financial Crisis: “An SEC investigation found that Deutsche Bank overvalued a portfolio of derivatives consisting of “Leveraged Super Senior” (LSS) trades through which the bank purchased protection against credit default losses."

- May 2015: Alleged Fund Fraud Exposes Cracks in Securities Pricing: “The trustees have determined that the valuation of the fund’s assets may not be reliable,” the board wrote in a letter to shareholders after [manager] Thibeault’s arrest that month.

- May 2015: We Tried to Re-Create JPMorgan’s Mutual Fund Returns and Gave Up: The bank’s impressive mutual-fund-group performance figures come with little explanation

- Mar. 2015: SEC Announces Fraud Charges Against Investment Adviser Accused of Concealing Poor Performance of Fund Assets From Investors: The SEC’s Enforcement Division alleges that Lynn Tilton and her Patriarch Partners firms have breached their fiduciary duties and defrauded clients by failing to value assets using the methodology described to investors in offering documents for the CLO funds, which have portfolios comprised of loans to distressed companies.

- Sept. 2014: SEC Finds Deficiencies at Hedge Funds: Shortcomings Include Valuation 'Flip Flopping'

- Sept. 2014: Pimco ETF Draws Probe by SEC: Regulators Are Probing Whether Returns Were Artificially Inflated

- Aug. 2014: FINRA Fines Citigroup Global Markets: "Citigroup priced more than 7,200 customer transactions inferior to the NBBO because the firm's proprietary BondsDirect order execution system (BondsDirect) used a faulty pricing logic"

- June 2014: Ex-Millennium Fund Manager Gets Four Years in Prison: "Former Millennium Global Investments portfolio manager Michael Balboa was sentenced to four years in prison for defrauding investors by inflating the value of Nigerian sovereign debt by $80 million." ... "Balboa, a London-based investment manager, was convicted of providing fake valuations to inflate month-end market prices on Nigerian warrants. The scheme generated millions of dollars in management and performance fees for which he earned as much as $6.5 million, prosecutors said."

- Feb. 2014: SEC Looking at How Alternative Funds Value Investments

- Feb. 2014: Danske Bank Faces Broader Probe of Bond Price Fixing in 2009: "The trades, conducted in February and March 2009, raised mortgage bond prices in a way that “harmed customers at Realkredit Danmark A/S,” Danske’s home-loan unit, the crime squad said."

- Jan. 2014: Federal Probe Targets Banks Over Bonds: Inquiry Looks for Deliberate Mispricing of Mortgage Bonds Key to Financial Crisis

- Dec. 2013: SEC charged a London-based hedge fund adviser GLG Partners with internal controls failures that led to the overvaluation of a fund’s assets and inflated fee revenue for the firms.

- Aug. 2013: 2 more targeted in JPMorgan's London Whale case: "Prosecutors in the office of U.S. Attorney Preet Bharara in the Southern District said Martin-Artajo and Grout manipulated and inflated the value of position marks in the Synthetic Credit Portfolio, or SCP, which the government said had been very profitable for the bank's chief investment office."

- Aug. 2013: SEC Charges Former Oppenheimer Private Equity Fund Manager with Misleading Investors about Valuation and Performance: "The Securities and Exchange Commission today charged a former portfolio manager at Oppenheimer & Co. with misleading investors about the valuation and performance of a fund consisting of other private equity funds."

- Dec. 2012: Deutsche hid up to $12bn losses, say staff

- Nov. 2012: KCAP fund, execs settle charges of overstating assets.

- Oct. 2012: SEC Charges Formerly $1 Billion Yorkville Advisors Hedge Fund With Fraud and Bogus Valuations

- May 2012: FINRA Fines Citigroup Global Markets $3.5 Million for Providing Inaccurate Performance Data Related to Subprime Securitizations: "Citigroup failed to supervise mortgage-backed securities pricing because it lacked procedures to verify the pricing of these securities and did not sufficiently document the steps taken to assess the reasonableness of traders' prices."

- May 2012: JPMorgan CIO Swaps Pricing Said To Differ From Bank

- May 2012: Ex-UBS Trader Sues After Firing for Mispricing Securities

- Feb. 2012: SEC Looking Into PE Firms’ Valuation of Assets

- Feb. 2012: Massachusetts Subpoenas Bank of America Over CLOs: examining whether Bank of America knowingly overvalued the assets in the portfolios in order to get the loans off its books

- Feb. 2012: Ex-Credit Suisse traders face US charges: Case relates to alleged CDO mispricing

- Jan. 2012: SEC Charges UBS Global Asset Management for Pricing Violations in Mutual Fund Portfolios)

- Dec. 2011: SEC Charges Multiple Hedge Fund Managers with Fraud in Inquiry Targeting Suspicious Investment Returns

- Nov. 2011: PwC and KPMG criticised over audits (of their clients' valuations of mortgage-related securities)

- Oct. 2011: Oversight board faults Deloitte audits

- July 2011: Polygon Faces Accusations It Used Tetragon For Cash

- April 2011: Report says Goldman duped clients on CDO prices

- April 2011: Wachovia cheated investors by inflating markups, SEC says

- March 2011: Buffett’s Berkshire Questioned on Accounting

- Feb. 2011: What Vikram Pandit Knew, and When He Knew It

- Feb. 2011: Mutual Funds' Muni-Debt Prices Are Questioned

- Oct. 2010: SEC Continues Crackdown on Overvaluations of Hedge Fund Assets

- Aug. 2010: Merrill's Risk Disclosure Dodges Are Unearthed

- May 2010: HK watchdog slaps fine on Merrill units

- April 2010: Legal Woes for Regions Financial

- Nov. 2009: Ambac Misstates Financials to Meet Minimums

- July 2009: Under Fire, NIR Group Switches Valuation Firms

- June 2009: Evergreen Pays Over $40 Million to Settle SEC Charges that it Overvalued Mortgage-Backed Investments

- April 2009: FHLB Executive Who Left Cites Securities Valuations

- Aug. 2008: "Large Number" of Banks Miss-Marked Assets, U.K. Regulator Says

- Aug. 2008: Financial Services Authority’s "Dear CEO: Valuation and Product Control" Letter

- July 2008: The Subprime Cleanup Intensifies: Did UBS Improperly Book Mortgage Prices? Several Probes Expand

- Feb. 2008: IN RE REGIONS MORGAN KEEGAN SECURITIES, DERIVATIVE and ERISA LITIGATION:"(g) The Fund's Board of Directors was not discharging its legal responsibilities with respect to “fair valuation” of the Fund's assets and had abdicated these responsibilities to the Fund's investment advisor, which had an inherent and undisclosed conflict of interest because its compensation was based on the amount at which which the Fund's assets were valued"

- Feb. 2008: AIG's bad accounting day

- Feb. 2008: OCC Supervisory Letter to Citi (identifies as one of two key concerns "CDO Valuation and Risk Management in the Capital Markets & Banking Group")

- Oct. 2007: Ex-RBC trader says colleagues mismarked bonds

- Oct. 2007: Pricing Tactics Of Hedge Funds Under Spotlight

- Aug. 2007: BNP Paribas halted withdrawals from three investment funds because it couldn't "fairly" value their holdings

- Aug. 2007: Goldman Disputes AIG Valuations and Office of Thrift Supervision Instructs AIG to Revisit Modeling Assumptions

- Jan. 2006: Deutsche suspends trader over £30 million 'cover-up’

- June 2002: An Analysis of Allied Capital:Questions of Valuation Technique

- Aug. 1994: Behind the Kidder Scandal: How Profit Was Created on Paper

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)